Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna just received a few hours ago the Nobel prize in Chemistry 2020 for “the development of a method of genome editing”, namely their 2012 discovery of the CRISPR/Cas9 genetic scissors which basically enables to “cut and paste” DNA. This scientific discovery has fueled an unprecedented biotechnology development in the past 8 years. When we started to analyze the genome editing patent landscape in Spring 2014, there were only 96 patent families(*) in our records in relation with CRISPR. We have now more than 7400 in our latest records – and adding an average of 200 more every month in 2020. What does this data tell us on who has taken advantage in engineering new life sciences solutions out of this amazing scientific discovery, now confirmed worth a Nobel Prize?

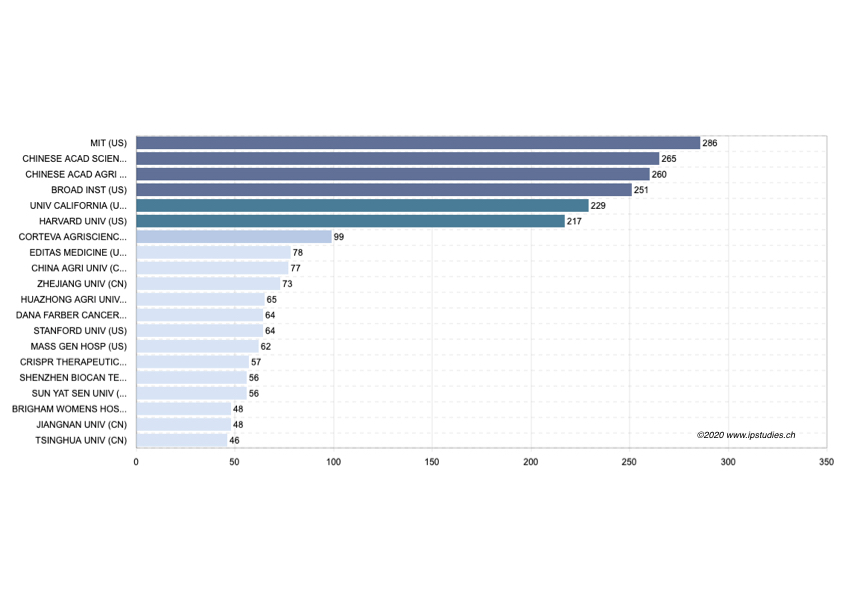

First, the high-level CRISPR patent landscape trends have been remarkably stable over the past 4 years, with continued patenting competition primarily among academic players in China and the USA. China very quickly joined the CRISPR race with a strong focus on the CAS9 technology for genome editing applications in particular in agriculture, hence the 3rd worldwide rank of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (42 institutes) in our landscape (**). In the USA, the home university of Jennifer Doudna, University of California, keeps on competing with its principal academic rivals MIT and the Broad Institute (of Harvard and MIT). Both license their core CRISPR technology IP to a number of large industrial players, such as DuPont in agricultural applications, as well as to a set of pioneeering CRISPR spin-offs primarily heading for therapeutic applications, namely Editas Medicine out from the Broad Institute, CRISPR Therapeutics initially funded by Emmanuelle Charpentier, and Intellia Therapeutics out from the University of California.

In the set of 7427 patent families from our latest CRISPR patent landscape records, 3078 address therapeutic applications, 996 animal modification, 1232 plant modification, and 541 bioproduction. More than 1850 institutes and companies worldwide have filed at least one patent application on their CRISPR R&D. Anyone pretending than patents are an obstacle to innovation should browse our data… just out of it, we can tell hundreds of R&D stories, from the evolution of their patent claims positioning over time. And all these innovations will become public domain within the next 2-3 decades. We have observed for instance the development of more than 50 shades of CRISPR in the past 4-5 years, as design arounds and/or improvements to the initial Cas9 discovery, to which only about 4500 patent families specifically relate in our latest records. In contrast, back in 2014, all the IP derived from the 2012 discovery was Cas9 specific; its most famous alternative protein, Cpf1, now already gathers 899 patent families in the current landscape.

However, commercial deployments are still made complex by the legal uncertainty around the unclear CRISPR licensing requirements in some jurisdictions, in particular for the above mentioned most popular CRISPR system variants. The initial CRISPR-Cas9 patent war between the Broad Institute and the University of California is still not over. Both parties keep on fighting primarily in front of the US patent office and the European patent office to kill or at least narrow down each other’s patent assets – there is no clear international winner to date, with oppositions and appeals to former opposition decisions still on-going at the EPO while the early patents from both parties still co-exist in the USA after having survived complex interference proceedings at the USPTO. While less publicized in the main media, the quest for ownership of the Cpf1 technology has also long been visible in our CRISPR patent landscape.

Despite this legal uncertainty on the some of the assets, we have so far recorded near 200 publicly announced licensing agreements, some exclusive, some non-exclusive, on a diversity of CRISPR technologies and application fields. More than half of those agreements were directly or indirectly issued from the competing Broad Institute and the University of California CRISPR IP portfolios.

There are only two nominees on the Nobel Prize; but Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier already paved the way for more than 16000 inventors worldwide to develop new solutions out of their discovery. This was just in just a few years… this is really impressive. Congratulations!

(*) A patent family is initiated by an initial invention filing at a patent office. In general, an invention will be ultimately recorded as different patents from the same “patent family”: one or more patent per country, depending on the patent owner’s investments in this country and the examination of by the national patent office. For instance, the initial invention by Doudna, Charpentier and their respective teams as filed at the US patent office on May 25, 2012 by the University of California has resulted into dozens of patent publications worldwide, several of which were just published at the USPTO in the past few weeks.

(**) Patent quantitative metrics are subject to some statistical bias in favor of Chinese players, due to their earlier patent publication practice compared to other countries. Indeed, many patent applications are published by the CNIPA 3 months after their filing in China, while they are kept secret for 18 months in most other patent offices worldwide and in particular at the USPTO, the EPO and the WIPO.

IPStudies is an independent patent analytics provider based in Switzerland. Our CRISPR patent and licensing monitoring data is available on a one-time or a monthly subscription basis. If our data is of interest to you, please contact us for more information on our products and services.